The Karimu Kids: School Is Not Enough—We Want Healthcare and Jobs for Our Families: Part 3 of 4

Categorized as: Africa, Education, Girls & women, Job Creation, Poverty Alleviation, Stories, Youth & Tagged as: Career training, High school, HIV, Karimu International, Microloans, Primary school, Tanzania on September 21, 2014.

Editor’s note: This cover photograph shows Bacho Village members of the first local microcredit group. These members, all HIV positive, shared a collective loan of $500 to invest in chickens. Two years later, they’ve paid back the first loan, expanded their business, and inspired a host of other small enterprises in the community. Sometimes, you’ve got to build an ecosystem. See updates below on just how their teachers and students did this.

Now that Bacho Village has strong resources to support their hard-working teachers and students from kindergarten through high school, the community addresses hygiene and healthcare for their most vulnerable: women in childbirth, infants, and HIV-positive members, and jobs-creation for the poorest parents through microcredit and farming collectives. Meet the teachers of Ayalagaya Secondary and two students: Florentina and Jackson.

By Suzanne Skees for Huffington Post

By Suzanne Skees for Huffington Post

Read Part 1 here.

Read Part 2 here.

Read the original piece on Huffington, here.

Ayalagaya Secondary School

Bacho, Tanzania: When you visit Bacho, it takes at least 30 minutes to walk about 3.5 kilometers along the rutted, red-dirt roads from Ufani Primary School to Ayalagaya Secondary.

In a country where just 3% of those among their parents’ generation have completed secondary school and beyond, the families of Bacho truly value education. This is shown by their spending: in a Karimu survey of nearly 300 local households, 80% earned far less than $1.25/day (the World Bank’s measure of extreme poverty). For most families, that comes from two (58%) or three (20%) different jobs. After food, the second place Bacho families spend is on school fees, followed by clothing, then medical. Still, according to the survey, as of 2009, only 28% of secondary-school age young people were enrolled in Ayalagaya. Given more resources, teachers, and classrooms, they hope to serve a far larger student population.

(Above) Bacho villagers build the houses that are vital in persuading teachers to accept and keep jobs in remote, rural villages. (Below) Catherine lives in one side of this completed duplex; another teacher lives on the other side. Funding and elbow grease also provided by Karimu.

(Above) Bacho villagers build the houses that are vital in persuading teachers to accept and keep jobs in remote, rural villages. (Below) Catherine lives in one side of this completed duplex; another teacher lives on the other side. Funding and elbow grease also provided by Karimu.

School board member Selena Martin notes that the secondary school, fed into by five primary schools and currently enrolling over 600 students, began with six classrooms and no teacher housing. “Now we have eleven classrooms, and we hope to add seven more, to reach eighteen,” she says. “We need more latrines, a kitchen, and three science laboratories—for physics, chemistry, and biology.”

Herself an entrepreneur who runs several small businesses such as cattle farming, maize grinding, and a rented guest house (“I am involved in so many businesses because each one pays only a tiny bit”), Selena made it through a convent school akin to secondary school, but regrets that her parents could not afford to help her achieve her academic dreams. That’s why she devotes her time to the high school today. “What I really want to see next is a technical college here; currently, the closest are in Iringa, Dodoma, and Dar [each a one- or two-day bus ride away]. We could offer training in computers, typing and secretarial, electrical wiring, carpentry—such skills could change the future.”

Constancia Kinyisi, history and Swahili teacher, was lucky enough to attend Korodwe College in the Tanga region. As Ayalagaya grows in population and reputation, she believes, “Our students can encourage others to get an education, too. Little by little, the parents in this area begin to see the need for education.”

The curriculum taught at Ayalagaya are the same as for all public secondary schools throughout Tanzania. The school motto is “Education for Creativity.” Constancia says, “Some [students] are very good in character; others are good in [academic] performance.”

(Above) The teachers of Ufani and Ayalagaya Schools collaborate across the kilometers of mud; (below) Headmistress Catherine Boay Buxay has dedicated her life to ensuring the youth of Bacho get the highest quality education.

(Above) The teachers of Ufani and Ayalagaya Schools collaborate across the kilometers of mud; (below) Headmistress Catherine Boay Buxay has dedicated her life to ensuring the youth of Bacho get the highest quality education.

Headmistress Catherine Boay Buxay has personally sponsored (paid the fees from her own pocket) several of her nieces and nephews through high school, and she has many current students for whom she wishes she could do the same. She shares a few of their stories: “Students like Alfred Sanka—he studies art and science and works very hard as a manual laborer to support his fees. There is Abrahim Nade: his father ran away from the family, and his mother lives far away from the school. So he had to do manual work to earn his own school fees. He planted Irish potatoes, and cultivates beans, to sell in the market. He rents a room here [in Bacho]. He even brought his little sister here to attend school, and he has become a father to her.”

Having grown up in this region the second eldest of twelve, Catherine was the only one in her family to attend high school and college. She studied Swahili and geography in Iringa and Dar es Salaam, and taught in the Hana district prior to coming to Bacho. She exemplifies a local who earned a high-quality education in two of the country’s biggest cities, including Dar es Salaam (the largest city of Tanzania at 4.4 million), and yet she returned to the rural village to teach here. She has devoted her entire career to the youth of Bacho. Although she does not have children of her own, teaching in a close-knit community feels that way. “You become a mother. The children belong to you in here,” she says, placing her fist over her heart.

These kids don’t mind getting their hands dirty to build the school that will open doors to their future.

Catherine lives in one of the new Karimu-built faculty houses near Ayalagaya School. She believes that in her school, “We are emphasizing the girls to be the same as the boys. We are changing society. What I want for these young people is simple: higher education, good houses, and a good salary.”

Florentina Mushi—age 17, form 4: Future Agronomist

For 17-year-old Florentina Mushi, farming is a science. It is the present and the future. Growing up on a family farm, Florentina helps to cultivate their maize, beans, and millet. She pitches in at home primarily with harvesting and cooking. She and her two sisters, four brothers, and mother and father, have the only solar lighting system so far in Bacho—and they have plumbing, too.

Growing up in a family that has more resources and uses them to bring infrastructure into the home, Florentina thinks about her place in the village and the world. “I think life is the same for both girls and boys,” she remarks. “I am happy because many teachers help me really to understand the material. However, it is a big problem that there is no laboratory at my school.”

That’s key for this student, whose favorite subject is science—particularly physics. She plans to study agriculture in college, because she wants to learn best practices for planting crops. She plans to move to Dar es Salaam for university and wants also to study geography, math, and economics. At one point she talks about being a teacher of agriculture; later, she says she will get married and manage a farm and business.

Meanwhile, she’s busy being a kid, playing netball with her girlfriends and enjoying time at home with her family. When she’s not doing gardening chores, she can be found studying or listening to music. She likes the “modern” kind.

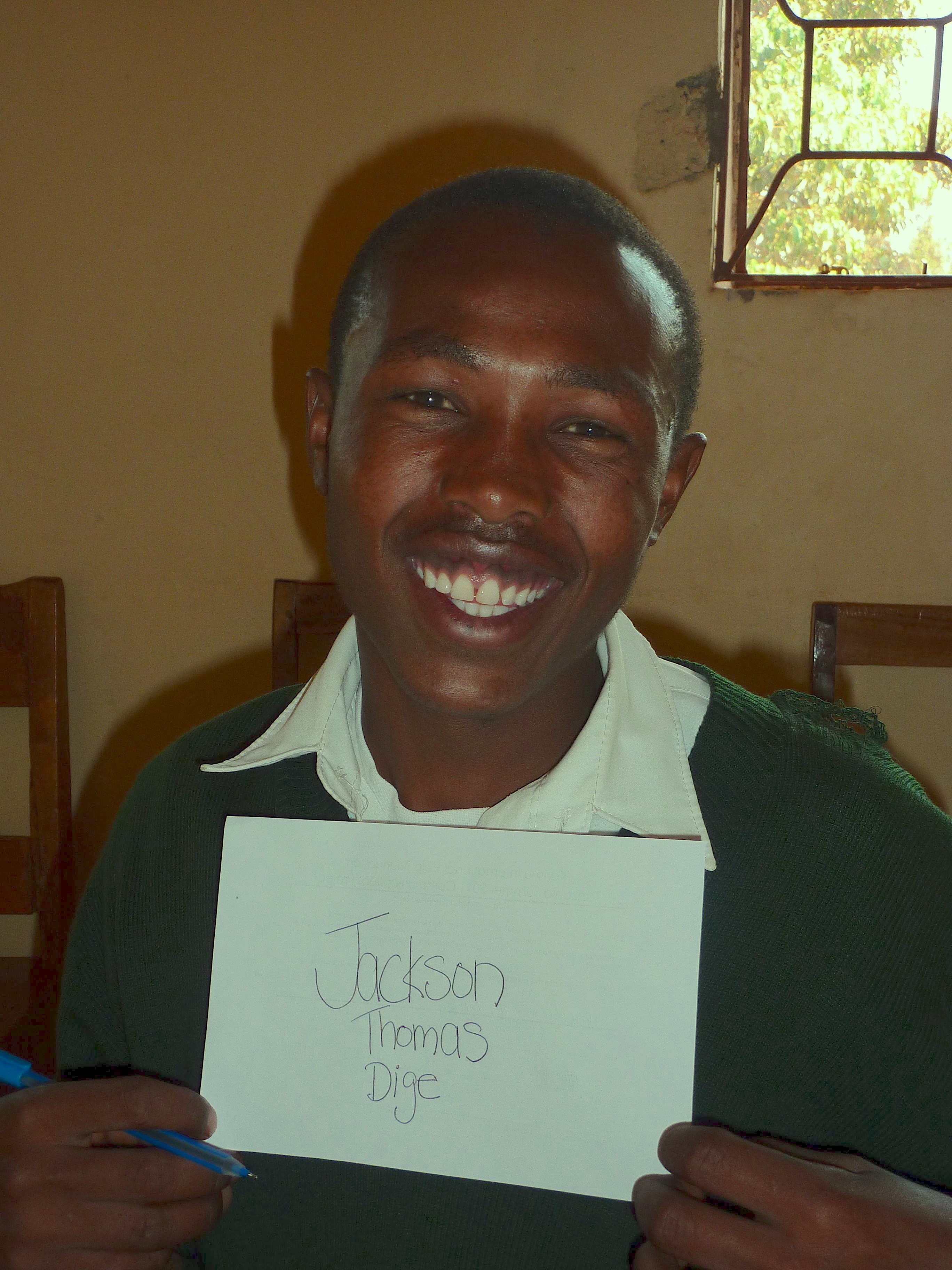

Jackson Dige—age 18, form 4: Future International Journalist

When Jackson Dige smiles, he lights up the school office where he sits in his uniform talking about his experience at Ayalagaya Secondary School.

His big family—parents, grandparents, three sisters, and five brothers—cannot scrape together Jackson’s school fees. But he’s found a way: Jackson tends a plot in the family garden, raising potatoes, onions, sugar cane, and bananas. On weekends, he bundles up his produce and lumbers an hour by bus to the nearest small city of Babati, to sell his wares at the markets. Proceeds pay his school fees.

“The biggest problem we have here is our economy,” he nods. “Still, I am happy. I have many friends.”

Jackson studies all the required secondary school subjects—geography, history, civics, Swahili, and English—but his favorites are geography and history. He struggles with math and chemistry. He spends time with friends but also reads newspapers and listens to music. “I like American music the best,” he chuckles. “Hip hop, reggae; you know, Rhianna and Sean Paul.” He wishes he could learn music, and he longs for a television to watch.

And there is no doubt in Jackson’s mind that he’s going on to college and then into the world beyond. If he gets the chance, that is. “I want to know how I can get help for my family, to improve the condition of the poor and get electricity [to the village.] For this I need the chance to continue my education.”

If you check back with Jackson in ten years, when he’s 28, “I will be an educated person,” he says. “Maybe a politician. Actually, what I really want is to be an international journalist specializing in natural disasters.”

The next projects completed by the Karimu-Bacho collaborative:

- Built two teacher houses for Ufani Primary School

- Built two teacher houses for Ayalagaya Secondary School

- Conducted village meetings to address sanitary practices, water treatment, and HIV

- Launched microcredit program for HIV patients

- Continued teacher development program for Ufani Primary School

- Brought fuel-efficient, smoke-reducing cooking stoves to 200 homes

- Completed clean water project for Ufani Primary School

- Installed plumbing (sinks, toilets, and showers) for local clinic that serves 40,000 people (previously there was no running water)

- Donated seed money to UFAGRO (Micro lending Farm Group)

- Built a kitchen and two fuel efficient stoves at Ayalagaya Secondary School

- Renovated two classrooms at Ayalagaya Secondary School

- Brought doctors to supply education about maternal and infant health

for KAMM group of midwives and nurses.

(Above) Dr. Susan Hughmanick, Karimu Board member and three-time volunteer, leads a maternal healthcare class for the KAMM midwives. (Below) The first microcredit group, UFAGRO, now has 47 members and has inspired several other such jobs collectives in the area.

Travel to Tanzania with Karimu to meet women volunteering as midwives (KAMM) for healthy births as they receive baby quilts crafted by women in the U.S.

Read Part 4 here.

Photographs by Suzanne Skees and Peggy Seltz. Video “Until We Meet Again” by award-winning documentary filmmaker Peggy Seltz.

LEARN more about the work of Karimu International Help Foundation and the village of Bacho here.

SHARE this story with your networks; see menu at top and bottom of page.

DONATE directly to give more students like Florentina and Jackson a quality education; or join Karimu’s hands-on work in Africa here.

SUBSCRIBE! Like what you see? Click here to subscribe to Seeds of Hope!