“Gun Laws Won’t Impact Us Here” in the Line of Fire, Say Peace Workers: Part 3 of 4

Categorized as: Stories on July 21, 2013.

In Chicago, the U.S. city that suffers the highest rates of gun violence and murder, a small team of unlikely adults employs a surprising technique to try to keep their kids alive. Part 3 in our 4-story series traces the Native American origins of the peacemaking circle and exposes the people behind the work at PBMR.

Read Part 1 here.

Read Part 2 here.

Read Part 4 here.

Making Peace the Way America’s Ancestors Did It

Chicago, IL: Peacemaking circles, a cornerstone tool of the restorative justice movement, bring together victims and perpetrators, estranged or upset family members—and on a weekly basis at The Center, members of opposing gangs. “Our goal was to extend hospitality to young people, who need us the most. We wanted to engender relationships with and between them, to cultivate a sense of self,” says Father Dave Kelly, director of the Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation (PBMR) restorative justice program in the Back of the Yards neighborhood. “If you have a solid sense of your self, then you will automatically value both yourself and the other.”

“Prison door:” line art by former Juvenile Detention Center inmate Javier Rodriguez, sketched on the back of a grievance form and given to Father Dave Kelly of PBMR.

The system of peacemaking circles originated from Native American traditions of conflict resolution through structured dialogue, in a circle, with members taking turns speaking and being heard. “The first thing we do is talk about who we are, not what we did,” says Dave. “We do several rounds of storytelling. For example, we might ask, who has been a mentor to you?—Everyone has had somebody, maybe a grandparent or teacher or minister. Suddenly, you’ve got something in common with this other person. They become more than the event; more than a victim or perpetrator.”

The juvenile center where PBMR youth serve time. In Illinois, inmates get transferred to adult prison on their 17th birthday.

The juvenile center where PBMR youth serve time. In Illinois, inmates get transferred to adult prison on their 17th birthday.

Recently in their neighborhood, a 17-year-old boy named Dante burglarized a home with two of his friends. What they didn’t know was that a police officer lived there with his family. The victim, a 45-year-old officer, found his windows broken, laptop and other items stolen, and his 4-year-old son too scared to enter the house. The son stayed at his grandma’s home for a few days while the officer repaired the damage. He was surprised to get a call from the PBMR Center, asking him to meet Dante in a peacemaking circle—but he decided to attend.

“Turns out, both men had grown up in the same neighborhood. Both had grown up without a father. Both the officer and Dante’s mother shared the same fears about raising a child in this neighborhood,” recalls Dave. “They discovered a strong sense of connectedness before they even got to the point of talking about the crime and how it was experienced.

“In every circle we get to the point where we ask the victim, ‘What do you need?’ Initially, the officer said, ‘Nothing. There’s nothing I need.’ Then he thought about it. He looked intently into Dante’s eyes and said, ‘I need you to go back to school.’ They discovered that they both loved to play basketball; and before we knew what was happening, the officer was inviting Dante to come play basketball with him at his gym. And they did. So, they became very close and in this case, the victim became the mentor.”

Dante and his police-officer mentor still shoot hoops, and Dante stayed in school because someone—unbelievably, the victim who forgave him—cared about his outcome. “What happens [in circle] is that relationships are restored,” Donna explains. “So often, it’s the relationships that are broken and once you restore them, everything else begins to fall into place.”

“It’s all about the power of the circle,” notes Cheryl, who’s conducted 80 trainings with The Center and works on-site with their members one day per month. “The youth are amazingly resilient. All we have to do is ask them, ‘What do you want? What are your dreams?’”

PBMR members use a circle of chairs around a round table bearing symbols of peace, along with a candle and a box of tissues.

PBMR members use a circle of chairs around a round table bearing symbols of peace, along with a candle and a box of tissues.

Finding Hope in the Heart of Trauma

Talking about what keeps him going day after day, year after year, Dave makes their work sound sensible, even easy. “You will see surprises among this population that you never expected: the tenderness of a young person in jail; the sense of humor in a kid who’s been violated.”

He pauses. “You’ve got to understand what’s different about these kids. They’re surrounded by violence from birth. They grow up knowingthey’re vulnerable: They have family and friends who’ve been killed. They themselves have been jumped. And here’s what’s critical: They know that the adults in their world aren’t going to protect them. Even in families with relative stability—two parents who are working and not addicted—they literally cannot protect these kids here.”

Art and afterschool program director Diana Rubio guides a PBMR member’s efforts as they translate trauma into images.

Art and afterschool program director Diana Rubio guides a PBMR member’s efforts as they translate trauma into images.

Social worker Diana Rubio and artist Cristobal Vargas—himself an ex-convict—run afterschool art programs in drawing, painting, and ceramics at the Center. Youth outreach workers Lamonte Lay (age 20) and Jonathan Little (age 22) have both served jail time and now work to keep other young men out of jail. Lamonte also edits a monthly newsletter (“Making Choices”) featuring sketches and poems by juvenile court inmates, Center members, and staff.

Long-time member Darius Clark painted a music mural on The Center hallway wall. He composes rap music and has recorded songs with his band. Having reached #9 on the Chicago hip-hop list for ReverbNation, Darius now finds himself advising other local youth who want to break in to the music business. His song “Non Sense” was featured by ABC News in their “Hidden America”series. Another group created a video drama about everyday danger called “One Shot,”starring former Center member John Jones, who’s now a full-time university student at Northern Illinois University.

“One Shot,” a film on daily life in gun-violent zones, created by members of The Center.

“This work—it just feels right,” says Denny. He knows he stands out as an older white male on these streets; yet he walks everywhere and frequents fast-food restaurants and the corner grocery store. “I recognize that I’m an outsider. It’s not a sense of, Oh, I know how to do this.—It’s just being willing to try.” Every Sunday at 9:00am, he says Mass with inmates at the county men’s jail. He also visits any youth who will see him—including a notebook full of regulars—at juvenile center, twice a week. He’s been visiting inmates for most of his adult life, in what he calls simply “a ministry of presence.” The priest from Ohio entered the seminary in his early teens, younger than most of the kids he now serves. “When I was younger,” Denny recalls, “I always wanted to have a big family. And now, I feel like I have one.”

Carolyn, The Center’s newest staff member, joined last November simply to be a support to the others. She’d met some of the boys, and their faces stayed with her until she joined the team. “My first week on the job was like being baptized in fire,” she says. “[on] my second day, my fellow staff member Mike and one of our youth members were held up at gunpoint in Mike’s car. The third day, we took one of The Center boys to a healing service, where we were asked to inscribe the names of friends who had died in the name of violence in the last year . . . Eight! He knew eight!—and one was his brother.” She says she’s concerned whether their members “ever have a chance to grieve, heal, or recover.”

Sister Donna with “Mothers for Peace” protestors; Sister Carolyn (standing, far R) with “Hope and Healing Circle” (click here for the story of the prayer shawls they’re wearing, and who in the Skees family crocheted them); Sister Carolyn doing beadwork with a PBMR member; and Sister Donna with two helpers in her flower garden.

Donna joined The Center in 2010, when executive director Father Dave called to say she was “the only person on the planet to do this particular work” in restorative justice. Just turning seventy, Donna was slated to retire. She’d worked with ex-convict women and homeless single mothers, many of whom struggled with serious drug addictions. She quickly got bored just doing part-time volunteer work. “I was restless,” she laughs, “so this work became my retirement plan.” She runs peacemaking circles for local high school girls and teenage mothers, and healing groups for stressed and grieving Center members’ mothers. Donna also talks to the boys, spends a lot of time listening, and does her share of joking around with teenagers twice her height. “Turns out, this is my life’s mission,” she smiles.

Mike Donovan (third from L) with a few of his driving-school graduates.

Mike Donovan (third from L) with a few of his driving-school graduates.

Mike, not in a religious vocation yet fiercely committed to The Center, finds this work as fulfilling as it is draining. He’d dabbled with easier volunteer work, serving meals at a homeless shelter, “But it wasn’t hard enough,” he laughs. “I was looking for something dirtier.” Starting one evening a week in prison ministry, Mike soon found his calling. “I loved it. I expected these kids to be so hard and closed, and they’re anything but: They’re warm, loving, sincere.” After just a few months, Mike saw the same kids cycling out and back into juvenile detention, their good intentions for change lost upon their return to the same environment. That’s when he decided to become part of The Center and offer youth a different place, and way, to be.

“My strength comes from the team,” Mike asserts. “These guys work 16-17-hour days, 7 days a week. And, the kids keep me going. Our mantra here is, We just don’t give up. We’re never giving up. But if you think it’s a straight line, you’re wrong. It’s the opposite of my [former] work with the IRS, where you could measure success. Here, it’s not like, you’re going to graduate from college, get married, and have two kids. Sometimes the goal is to be alive by the end of the year.”

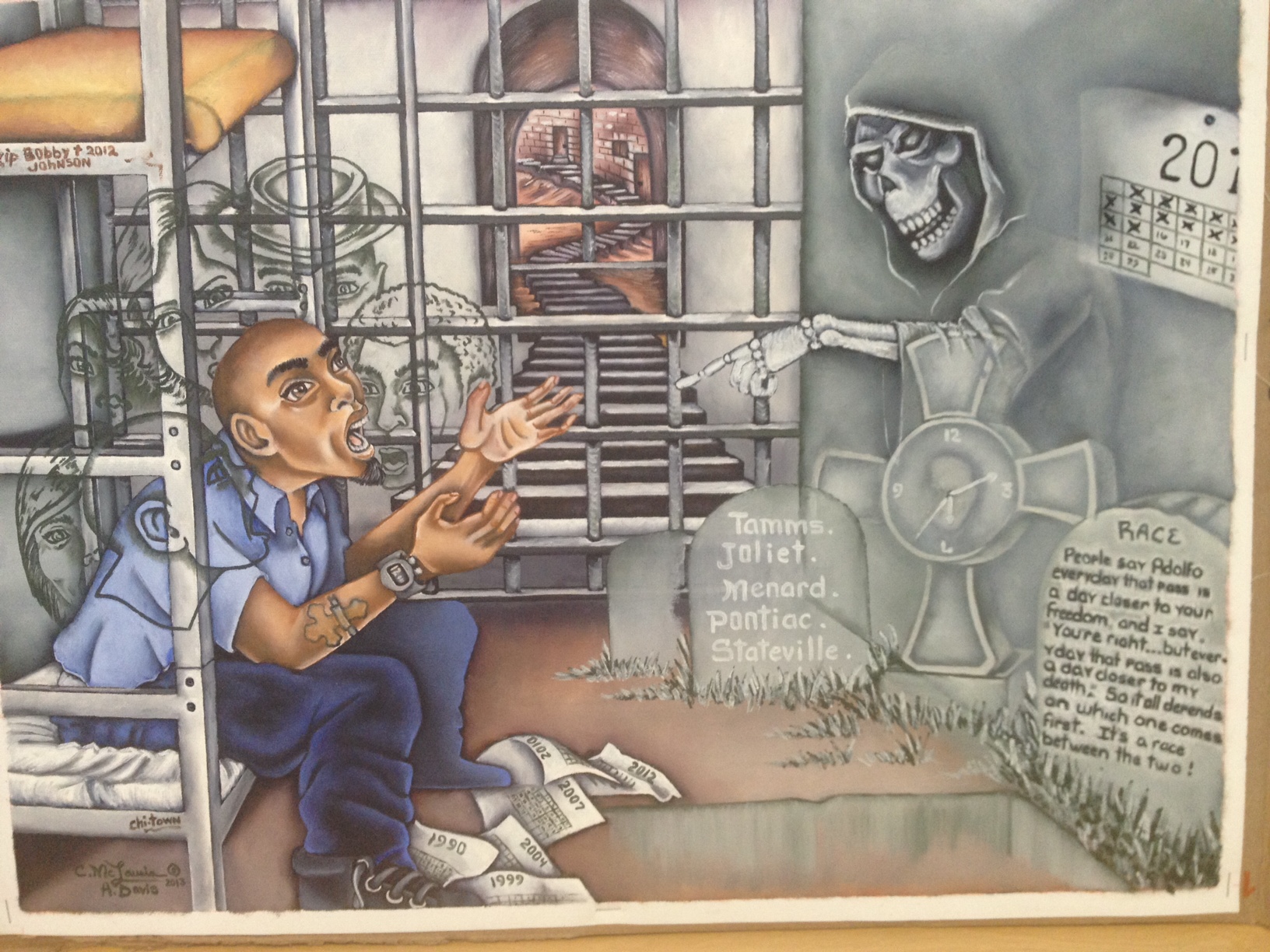

“Life,” an original painting by PBMR member and inmate Adolfo, whose hope inspires Father Dave on the “outside.”

“Life,” an original painting by PBMR member and inmate Adolfo, whose hope inspires Father Dave on the “outside.”

Staff members share a cluster of cubicles in the same large, open room that houses the art studio. Where Dave sits, he’s positioned a drawing at his exact eye-level that he says was created by his “biggest inspiration,” an “lifer” inmate named Adolfo. “He does brilliant [art]work, and every time I visit him, I am just blown away by his positive attitude,” Dave shakes his head. “Adolfo is my role model. If he has the hope he has, how can I possibly stew in my own juices here?”

Prison facts:

- 2.2 million incarcerated in the U.S. right now.

- Incarceration can cost tens of thousands per inmate per year—equal to an elite university education.

- 2 million American children are growing up with parents in prison

- Illinois is one of ten U.S. states to send 17-year-olds to adult prison . . . on their birthday

- Chicago has spent $2.2 billion on schools and $2.7 billion on incarceration since 2000

- 52 schools in Chicago will close this year—most of them in African-American neighborhoods

(Sources: Harvard Magazine, Chicago Youth Justice Data Project, Chicago Reporter, Community Justice for Youth.)

What might work:

- Mentoring: one person to support and accompany a youth growing up

- ID cards: in hand for every youth who enters/exits the court system (many do not have birth certificates or ID cards)

- School enrollment and attendance: on the first day out of juvenile center

- Visitation: improve rights for families; give them more time for in-person visits and free telephone calls, as many do not have telephone service at home

- Peacemaking circles in schools: for conflict resolution

- Peacemaking circles in court: as a precedent to, and possible replacement for, trial—if all parties reach satisfaction with outcome

- Peacemaking circles for families: to heal and cultivate relationships before, during, and after prison sentence

What Chicago’s youth say they want:

- Free bus cards to get safely to work, school, and programs

- Safe space to be afterschool and weekends that’s open, with sports/recreation

- Cultural sightseeing in their own city, to places they’ve never been

- Community centers for them and their families to spend time and be safe

- Girls asked for mentors who wouldn’t lecture them about teen sex and pregnancy

(Sources: Cheryl Graves of the Community Justice for Youth and Dave Kelly of The Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation/PBMR Center.)

Photographs and line art courtesy of PBMR and Suzanne Skees.

LEARN more about The PBMR Center’s holistic care of at-risk and incarcerated youth here.

SHARE this story with your networks; see menus at top of page and below this list.

DONATE directly to provide more youth and families with a safe space to heal, here.

SUBSCRIBE! Like what you see? Click here to subscribe to Seeds of Hope!