Haiti Field Visit: Back to School with Anseye Pou Ayiti

Categorized as: Caribbean, Education, Grantee, Latin America, Our Partners, Stories, Youth & Tagged as: Community based organization, Corporal punishment, Critical thinking, Dimagi, Gates Foundation, Haiti, Leadership, Nedgine Paul Deroly, Obama Foundation, Paul VanDeCarr, Slavery, Stealth grantmaking, Working Narratives on September 22, 2018.

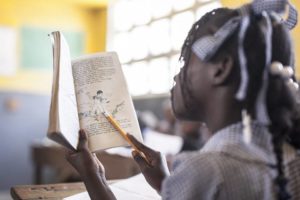

Editor’s Note: Anseye Pou Ayiti (or APA, Kreyòl for Teach for Haiti) is a nonprofit organization that recruits and equips local teachers in rural primary schools to elevate students’ learning, transform classrooms and communities, and build a Haitian-led movement of civic leaders to spread educational equity.

APA has been our partner soon after their founding in 2014, after a four-year process of listening to teachers, students, and families share what’s needed in the nation’s education system. Because they began with deep listening and baseline metrics, they leapfrogged over much trial-and-error and needed only further financial support to expand to more Haitian schools. For us, that was a no-brainer.

We discovered them in 2015, thanks to our stellar human network—in this case, Paul VanDeCarr, storyteller extraordinaire who became part of the Skees family through our past partnership with his nonprofit organization, Working Narratives. In what’s become our typical “stealth grantmaking” style, we researched APA and elected to support them before offering our multi-year, paperless, unrestricted “Seed” grant.

When that Seed grant had finished, APA had measured base points and impact metrics, adapted programs to fit community requests, reached student-passing-rates several times higher than national norms, and formed partnerships in new communities. This was an obvious case of a social enterprise ready to scale, and we awarded APA with our largest “Catalyst” grant.

Yet we’d supported them from afar for four years, relying on video calls and emails to observe and applaud their work. We niggle over every dollar of our budget and pride ourselves in keeping expenses low by working from home—thus, global site visits had remained beyond the reach of most of our volunteer board members, all of whom work hard in primary jobs to support our families.

Then this year, along came a rare opportunity—the JasmineHugh Heart Fund, a matching-grant program (privately funded so as not to detract from our grants) that allows board members to raise a portion of the cost to travel with our families to visit partners face-to-face. That enabled two board members—Sally and me—along with our families, to visit APA in July. Spending time with them convinced us of the validity of what we’d observed across the miles in our virtual relationship with their team. They were, in fact, even more passionate, dedicated, and delightful than we’d expected.

APA crafted a schedule to maximize each moment, visiting two schools, conversing with students and teachers, getting to know the APA team, and absorbing lessons learned from a teacher-leader panel discussion. We also shared a lunch of traditional foods: grilled chicken, national rice, Haitian macaroni and cheese, and fried plantains. The theme of the day reflects the mission of APA—to cultivate the innate culture and strengths of what co-founder and CEO Nedgine Paul Deroly, a “community-minded rising star” fellow with the Obama Foundation, calls “mighty Haiti.”

Anseye Pou Ayiti’s teachers believe they can unleash leadership and prosperity for their country through quality education for all.

Anseye Pou Ayiti’s teachers believe they can unleash leadership and prosperity for their country through quality education for all.

By Suzanne Skees

Skees Foundation members with APA Co-Founder and CEO, Nedgine Paul Deroly (2nd from R).

Goal: Equip and Retain Talent

APA wishes to “dispel any notions of poverty dictating the true potential of a nation.” They intend to:

- Transform education indicators so that enrolling in primary school without completion is no longer the norm for children in underserved schools.

- Improve student outcomes so 100% of students pass the national exams and pursue secondary education.

- Invest in top Haitian talent for the long haul, so their alumni ambassadors remain in Haiti and fill a critical gap in local capacity. APA alumni ambassadors will be career teachers driving groundbreaking student success, school leaders, instructional coaches, policy makers, and members of Haitian philanthropy and business sectors who continually promote equal educational opportunity for all Haitian children.

According to their theory of change, improving the quality of education and rates of matriculation for Haitian students will increase job-readiness, leadership efficacy, and skills of Haiti’s workforce, resulting in higher outputs and GDP.

Haiti: The Africa Next Door

And that’s how we experience the country: As we absorb the somber history of slavery in the National Museum and generations of natural disasters, political corruption and mismanagement, racial oppression and systemic poverty, we feel alternate waves of guilt (as Americans, who’ve done Haiti no favors) and rage (as global kin, acutely aware of how unjust is its plight) . . . But as the our weeklong visit progresses, something else takes over: admiration. We share meals, conversations, World Cup games, and an authentic vodou religious ceremony . . .

And the more we get to know Haiti, the more we see Africa. It’s the family values and unbreakable resilience, the innate kindness and pervasive spirituality. And it’s more than DNA, which links 95 percent of Haitians to Africa. Despite being trafficked as slaves, abused and assaulted, and then shunned by the global community upon achieving national independence in 1804, Haitians retain an unshakable strength, hope, and joy that only makes sense if one knows their motherland, Africa. Haitians are also unapologetic about the pride in their African roots. And with Haiti just seven hundred miles off the coast, we could say it’s our Africa, next door.

APA works to repair the frayed social fabric of Haiti and create pride through deep community engagement—including parent associations, teacher-leader and student-leader celebrations, and a peer-learning program for APA alumni to spread the movement across the nation. Read our coverage of their work here and here.

“Depth is scale,” claims APA. That means the deeper they go into each classroom and community, the broader and more sustainable the impact will be.

Using technology to track progress, APA partnered with Dimagi, Inc. in 2015 to create and deploy a customized mobile application that gathers data every two weeks which assists with coaching and monitoring progress of teacher-leaders and students. There is now international interest in this powerful tool, with APA selected to present the learnings from their mobile app during an upcoming mobile education symposium in Washington, D.C.

Change from Within

When we arrive to Gonaïves to begin our day with the APA team, Nedgine jumps into our van to meet us. We’re an hour late, after having spent four hours inching out of Port-au-Prince traffic into the countryside. “We co-created this movement with our communities outside of the capital city because our culture and customs are most intact in rural Haiti,” Nedgine says. “We wanted to tap into that power, those assets in transforming the education system.We didn’t start our own school because real transformation is in changing what exists—changing from within.”

As a result of this belief, APA deliberately chooses to work with existing schools. Also, to create an easily replicable model for quality education enables regions across the nation to see the possibility of adopting new practices and maximizing human resources they already have. This approach of bringing out the talent and leadership inherent in educators and students reflects a larger vision, an asset-based approach to social change. APA gambled that those already in the school system would blossom if given resources and confidence; and they were right.

Community “Open Forums”

APA holds community forums, like a recent one to which three hundred people came to talk about the tradition of corporal punishment—illegal but still the norm. “We asked the community, where did this tradition come from?” recalls Nedgine. “Not from Haitian or African culture; rather, from imperialism and colonial traditions imposed upon the education system. When teachers see it this way, they’re open to change.

A teacher-leader confirms, “We need to understand the roots of abuse and where they came from, and help the community learn where they can go from here.”

Nedgine reflects, “We want to form a stronger connection between the classroom and the community. One teacher-leader created a phone WhatsApp group for the students, now it’s parents who use it constantly to communicate, learn from, and push each other to get more involved. Now those parents are proactively working to bring more neighbors and friends involved in the school.. This is how we know the community needs and wants more local leadership.”

Parents’ Perspective on Changes in Their Students

One mom says reports, “My child is so comfortable with the teacher. He’s more motivated and really working now. Life for [these students] will be different in the future only if they hold onto their principles and values; otherwise, they could become vagabonds.” She would do anything for her son. “I’m watching over him. His dad is absent, but I am here. Even if I don’t have a lot of capacity, I want to help him however I can.”

Another adds, “My son is always talking about his teacher at home. He failed last year, but this year, I can already tell that he’s going to pass. He has far more motivation now. I hope he becomes whatever he dreams to be. I would be so happy. I’ll do whatever I can to support him—with funds, advice, and making sure he takes his education seriously.”

Equipping Students for Academic Success and Good Citizenship

Sitting together in their open-air school, we turn to the students to ask for their input. A fifth-grade boy named Bedrigue says, “Either my old school was too easy, or they were all cheating. At this school, I have to really work hard. I’m really learning now. I’m putting in an honest effort.”

His classmate tells us that his teacher always takes the time to explain everything. “That makes school easier now.”

Class President Navély rehearses his graduation speech for with APA Co-Founder and CEO Nedgine Paul Deroly at his school in Gonaïves, Haiti.

We meet Navély, the class president. His mom, who travels back and forth from the Dominican Republic for work, remarks that he used to be “rambunctious.” Now, he holds himself with calm assurance and practices for us a part of the speech he will deliver at the graduation ceremony this weekend.

Planning for Success by Visioning Your Future

A key component of APA’s teaching approach is their annual visioning exercise. Starting as young as kindergarten, all students respond to prompts to discover their vision of themselves at age twenty-five. Many are so inspired by this exercise, they have taken a new name for themselves, e.g., “Agronomist Naichka” or “Engineer Jonathan.” Then they plot out a course of action to garner the skills needed for their career, and their teacher-leader guides their learning. The process begins with a question: “What will fulfill you?” and the exercise builds a foundation of pragmatic means toward that end.

Navély remarks, “The visioning exercise was a big thing to set my expectations for myself. First I decide what I want to be; then I get input from my family, community, teacher, and school. I take home a cardboard version of the written exercise as a memory of my personal vision. I’m going to be a doctor AND a lawyer. I like all subjects, especially science.”

Sarah talks about what American schools can learn from APA’s Haitian curriculum.

The two young women from our family, third-generation Skees Foundation members, are very impressed with the visioning exercise. Twenty-year-old Michaela, a junior at the University of Vermont (UVM), says she could learn from these students, as there is nothing like this at colleges in the U.S. Sixteen-year-old Sarah, a high-school junior in upstate New York, says the U.S. places emphasis on taking exams and getting high grades rather than knowing what you want to do (in your career) and what it takes to get there. They both feel that American students could greatly benefit from APA’s visioning model.

(L to R) Student leaders and their teacher talk with SFF director Sally Skees-Helly.

“I Love My Teacher”

We visit a school where we interview a teacher-leader named Esther Oxilas, who is thirty-nine. She teaches fourth grade and just won her school’s “teacher of the year” award. “I love to teach,” she tells us with a smile almost wider than her face. “But there is no career without training in the work.”

The principal, Ms. Myriame, pops in to greet us and provide context. “Kids here are underserved,” she says. “Many of their parents have abandoned them to move to Brazil or Chile to work.They have to leave them in the care of a neighbor or relative. This has a psychological impact on my students. Sometimes, the parents send remittances from abroad that get intercepted by the family. But we never turn a student away due to financial hardship. We give them a free uniform, food, whatever we can . . .”

“Since Esther has been coached with APA,” Miriam continues, “she has a 100 percent pass rate in her classroom. One Friday per month, our school organizes peer coaching sessions so the APA teacher-leader can share what she’s learned with the rest of the faculty. Even during recess, kids used to fight with each other, and now they do not.” She wishes APA could reach all ten geographic departments of Haiti.

Esther reflects on how her teaching style has changed. “I used to teach just to teach [facts]; but with APA it’s not only about following the curriculum, but also to follow the evolution of the students.” She now encourages students to participate in dialogues and discovery.

“Teaching doesn’t age you,” she insists. “If you’re in it for the money—ugh! But if you love what you’re doing, you won’t get old.” Esther has been teaching for five years, “but it feels like my first year.”

According to Nedgine, a teacher must be far more than a teacher. “In our community context, you’re not doing your job,” she says, “unless you’re being invited to baptisms, weddings, and funerals.”

“Learners Are Leaders”

We meet two of Esther’s students, both of whom cried when they learned that their teacher would not be with them when they move up to fifth grade this year. A nine-year-old boy named Bens Holly tells us, “There is nothing that my teacher has ever done that I do not love.”

He has a clear vision for his future. “I was like a maniac, always hitting people. Any little thing could spark me to fight. And I used to think I was superior. Now I realize I was abusing people. I like to play soccer and watch the World Cup, and to listen to music. In the future, I want to learn and teach all the way until our country changes completely to become better. I want to design cars that don’t use gas—cars in all colors—that can go everywhere . . . ”

His ten-year-old classmate, a girl named Noslande, adds, “I’m a twin and I used to fight all the time with my sister, but now I collaborate. If she asks me to borrow something, I give it to her. And we learned that we shouldn’t throw garbage into the street, because that is like our living room, our home. Now, I want to be a role model; and in order to do that, you have to do it everywhere you go. I’m going to be a doctor and work in a walk-in clinic where I can take care of everybody. . . . My hobbies are dancing and listening to gospel music.”

Education in Haiti by the Numbers

Before APA: “Quality crisis:”

- 20% of Haitian primary school teachers are formally trained

- 30% pass primary (with APA,85%)

- 10% pass secondary

- 1% get to university

With APA: Local civic leadership by students, teachers, and parents:

- 66 partner schools across Haiti during 2018-2019 school year

- Over 5,100 students served

- 90 percent reduction in corporal punishment across APA partner schools

- 10 collaborations with civil-society organizations to advance learning for Haitian children

Top-Down from Gates Foundation to Haiti

The Gates Foundation, which just announced a new round of $92 million in education grants within the U.S., has shifted their strategy toward replicating APA’s model—perhaps without even knowing it. According to Howard Blume, writing for the Los Angeles Times, “Experience seems to have taught them not to impose so much from outside. They want to create networks of schools that will work together, with help from experts, to solve problems—and then share strategies and research.” Maybe they can go back to school just like we did, and learn from APA how to catalyze quality education from the ground up.

“If Not Me, Then Who?”

A panel discussion of APA teacher-leaders mulls over the topic of change—both internal in them and external in their country. Their teaching styles have shifted away from rote memorization and toward engaging students in critical thinking and inquiry, as well as how to work in groups.

Transformational leadership, they tell us, begins with changing your own mindset. “Many of us were not leaders before we entered the APA fellowship. Before, we had a complete lack of hope and despair about Haiti. Now, we believe we can choose to change,” says Emmano Medina. She cites perseverance, nurturing, and dedication as natural results of APA’s training.

“Change is the emblem of this movement,” remarks Jonathan Michel, “And I want to be a part of that.” He’s been teaching for eight years but this year he’s enjoyed a 100 percent student pass rate for the first time. “APA is a revolution.”

“Before APA,” remarks Phabiana Jean, “the students didn’t come to school regularly. Now they come in every day, and I can’t miss a day. I have to be there for them . . . I feel connected to my students now through love and friendship. I am sincere with them.”

She describes the shift in her school after positive discipline techniques. (After APA workshops for teachers, corporal punishment was 90 percent reduced.) “I have thirty-two little kids running around my classroom,” she laughs, “and I have to stay calm. I don’t want to hit them. Instead, I sing and dance with them, have a conversation about how we are all one family; you are brothers and sisters and cousins to each other.”

Jonathan Michel quotes Nelson Mandela: “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” He believes that education improvements can dramatically affect Haiti. “I never dreamed I’d be a teacher. I was in university when APA came in and gave a presentation. I applied and I gave my whole heart to this movement. I need to do this for my country. It has to be me.”

Take a virtual visit to Anseye Pou Ayiti here.

Or, dance with teachers and students in this celebratory video of APA in action this year.

Photographs and video courtesy of Anseye Pou Ayiti.

LEARN more about Anseye Pou Ayiti here.

SHARE this story on Facebook and Twitter; see menu at top and bottom of page.

DONATE directly to Anseye Pou Ayiti here.

SUBSCRIBE! Like what you see? Click here to subscribe to Seeds of Hope!